MUNITIONS SHORTAGES IN UKRAINE AND IN HISTORY

A FOURTH OF JULY FIREWORKS SPECIAL! Why are there always munitions crises after wars begin?

Of course, there are munitions shortages —-on both sides—in the war in Ukraine. This is a recurrent phenomenon even in the most anticipated wars. The most clever military and civilian leadership do not seem to be able to learn from history that their forces are going to run short of stuff to launch at the enemy.

In the Ukraine war, the most acute shortages for Ukraine and the western allies, and for Russia and its friendly countries, are in the stocks and production capacity for “precision” rockets and artillery rounds. Also in short supply are spare parts and technicians to fix the rusted or neglected materiel sent to the front.

I put “precision” in quotes because if a 155mm artillery round or a HIMARS rocket lands just a few meters off your exact location, the round will still affect your well-being or morale. It’s just a term of art, like “military efficiency”.

There are a lot of well documented precedents for munitions and “systems” shortages. ”Systems” lends a neutral, considered tone to arguments over military equipment procurement and to budget disputes over which military branch gets what and how much.

“Systems” have more public affairs appeal. Politicians, generals, admirals and corporals do enjoy being photographed and interviewed in front of fighter jets, aircraft carriers and tanks. Repetitive piles and racks of artillery rounds and near-indistinguishable rockets are not so appealing. Systems are for dramatic brandishing. Munitions are for hourly bloody use over months and months of fighting for decisive advantage or surrender.

The last time I recall being briefed on an acute munitions shortage was shortly after the 2011 NATO-led intervention in Libya, which resulted in the death of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi, the Libyan strong man and terrorist group sponsor. I was asked to lunch at the UK Consulate in New York in my capacity as a Financial Times columnist.

Among the briefers present was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Tugendhat, who at the time was Military Assistant to the Chief of Defence Staff at the Ministry of Defence. His career has prospered since then, and “Tom” Tugendhat is now a Conservative MP and Minister of State for Security of the UK.

At the New York Consulate lunch Lieutenant Colonel Tugendhat spoke of how the UK (and, I believe, French) military elements involved in the Libya intervention had found themselves short of munitions for their operations after only a few days of air sorties and, not spoken of, special operations on the ground.

While the conversation at the Consulate was off-the-record (Chatham House Rules), the US public had already been told through Washington media leaks that the US Navy and/or Air Force had at least partially made up for the munitions shortages by lending the necessary fireworks. Discreet approval had been given, and modest credit had been taken by the Obama White House.

In the light of subsequent events, there has been some chin-stroking and reconsideration of the Libya intervention by the NATO allies. The action may have contributed to the ongoing Migrant Crisis in the Mediterranean and elsewhere on the borders of Europe.

However, the “surprise” munitions shortages that were exposed by the original, brief, Libyan intervention did not appear to lead to official follow-on reflection or to remedies in procurement and maintenance of adequate military stockpiles by the NATO members. The European allies are still mired in ineffectual operations in the Libyan sand trap and have not yet figured out how to replace Col. Qadaffi’s cork in the migrant pipeline.

So, when the much-predicted current phase of the Ukraine-Russia conflict started in February of 2022, the western allies quickly found that they were hard pressed to supply the hard-fighting Ukrainians with the Javelin missiles, HIMARS rockets, artillery rounds and well-maintained expendable kit that was needed. The response from the allies was swift.

Well, at least the public affairs officers and the consultants were swift. Committees were formed, studies have been initiated and even published and disseminated. Much of the detail of the munitions shortages is secret, of course, particularly because it makes important people look bad. But what with all the usual bureaucratic, national and corporate rivalry there seems to be enough open-source intelligence out there to get a sense of what’s going on with munitions.

As history (and MOD/DOD officials) tried to tell us, it is not easy to quickly find the staff, facilities, materials and logistics trains to get munitions reliably produced in adequate quantities and sent to whatever the front is. And as usual, there’s another enemy, or, rather, strategic competitor on the horizon, i.e China.

There are not enough semiconductor chips, silicon steel rolls, titanium ingots, fine chemicals, equipment to retrieve and repair damaged armor and special vehicles, or production lines to get munitions made quickly enough. There are, though, Thank God, enough consultants, think tanks, parliamentary, congressional and administrative staff to supply rationales, blame for previous governments and administration, prepared speeches and scripted off-the-cuff remarks for distribution to the political hacks and media reptiles.

And there’s lots of History. For example, there was the famous (at the time) “Shells Crisis” of 1915, when the British and French armies were caught short of artillery rounds after the first horrific weeks of World War I, which had started in August 1914. There was a similar crisis in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but under stricter censorship and with less vocal opposition politicians and critical journalists.

There were a lot of losers from the Shells Crisis, particularly among the soldiers, sailors, civilian property owners and taxpayers who were at the wrong end of the shells that were produced and delivered. But there were some winners.

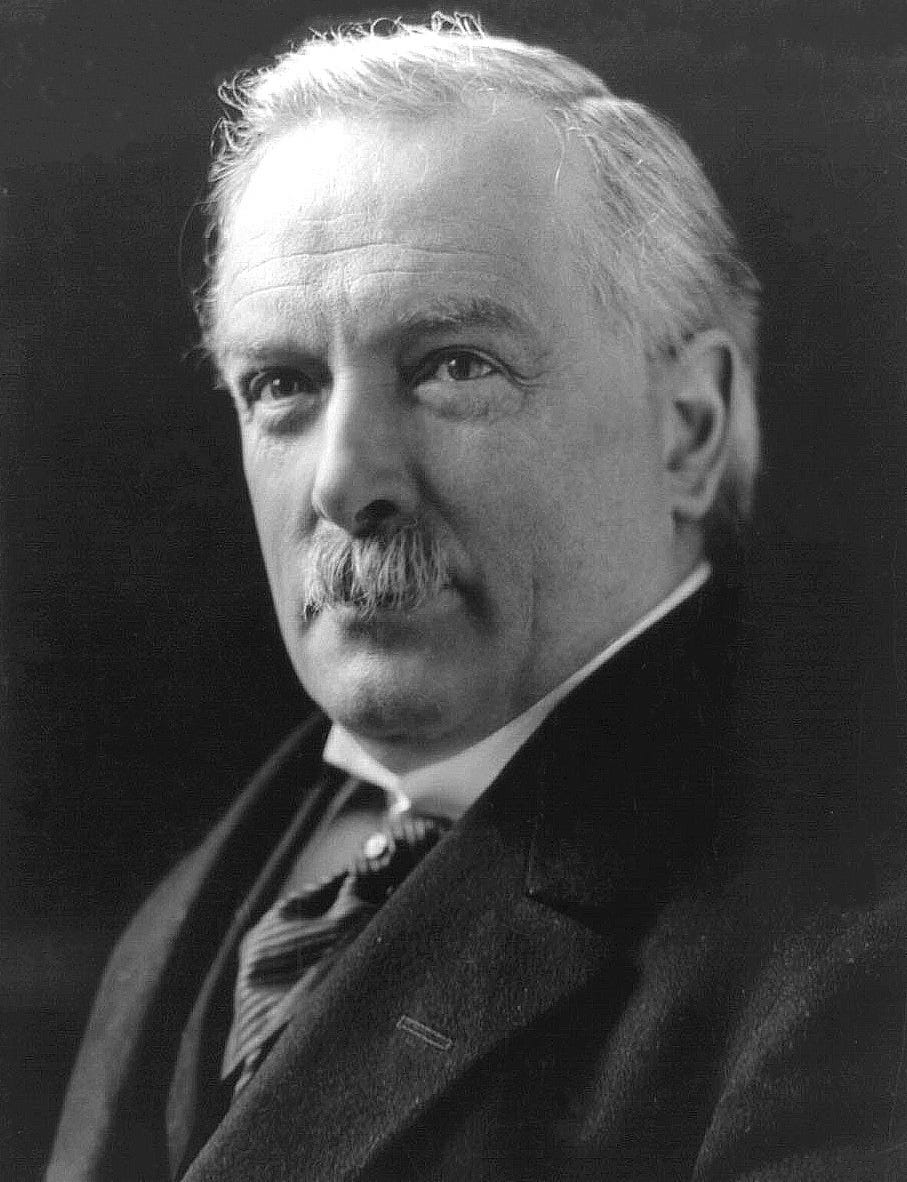

Among the winners in the UK were David Lloyd George a parliamentary politician and Welsh lawyer. In France, the winners included André Citroën, an industrialist and French Army artillery officer.

Mr. (as he was then) Lloyd George was, after he brought attention to the (usual and acute) munitions shortages on the Western Front, appointed Minister of Munitions, a sort of shells supremo. The energy Lloyd George brought to marshaling the engineering and manufacturing systems needed to produce enough shells brought him acclaim, and, in short enough order, an appointment as Prime Minister and political war leader of the UK. After the (it turned out, temporary) peace, he continued a remarkable political career and eventually wound up with a hereditary peerage. Not bad for a Welsh lawyer!

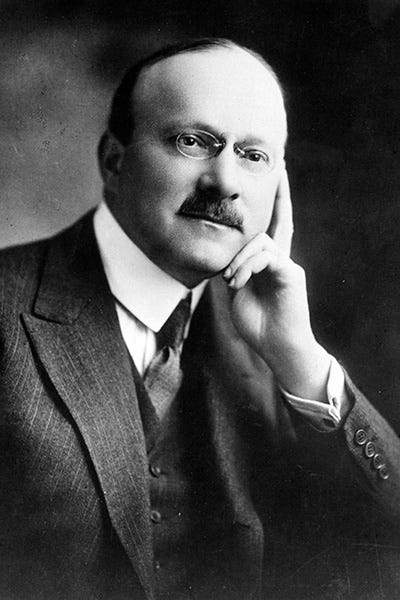

On the French side there was André Citroën, a graduate of the prestigious École Polytechnique who went on from his family’s mercantile background (the Citroën’s were originally Dutch) to co-found an automobile parts supplier and machinery company. He had apparently met (briefly) Henry Ford, who even then was becoming famous as a mass manufacturer of automobiles.

At the start of WWI, Citroën had joined the French Army, which was natural as the École Polytechnique is a military as well as an engineering school. He was assigned to the artillery branch, where after the opening weeks he witnessed the French version of the Shells Crisis. Not enough munitions.

Citroën appealed to the frustrated French military and wartime leadership, asking for the authority (and the contracts) to solve the munitions shortages. He dropped the Henry Ford name, applied salesmanship and political skills along with the necessary engineering words, and got himself a deal, or deals.

France got the shells, lots of people were killed, and Citroën’s fortune and name as a brilliant engineer and manufacturer were made. He went on to sponsor the design and development of the Citroën Traction-Avant, one of the iconic autos of the 20th century (and the favorite vehicle of the Gestapo in France).

Unfortunately, from the money point of view, André Citroën effectively bankrupted the auto company when he ran into initial production problems with the Traction-Avant. However, the Citroën firm was too important to France to allow it to be liquidated when the cash crisis hit the company in 1935 and the Michelin tire company family provided a bailout in return for a controlling equity share. The marque is still active as part of the Stellantis global auto group.

It may be worth noting that Henry Ford himself was firmly anti-war (and anti-Semitic). And his “innovation” of the auto assembly line was derived from the English invention of the “transfer line” for serial production. The transfer line in turn could be traced to the “disassembly” line used by Chicago meatpackers to chop up and sort animal carcasses.

The revolution in 19th and 20th century manufacturing centered on assembly (or transfer) lines and standardized parts has been traced by American historians to Eli Whitney (notional inventor of the cotton gin) and his allegedly interchangeable parts-based musket factory in New England at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century.

It is more credible to me that Whitney and other early American manufacturers were “appropriating”, copying, or reverse-engineering a lot of British and Continental European machinery and techniques. Some of this intellectual property …ahh…appropriation was encouraged by Thomas Jefferson, who as US Ambassador to France had observed the work of French artisans such as Honoré Blanc and the artillerist Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval.

And while Henry Ford was the most famous public face of mass manufacturing by the time of World War I, an arguably more important figure among manufacturing professionals was Frederick Winslow Taylor. Taylor (of “Taylorism”) was an industrial efficiency expert who inspired several generations of time-and-motion staff who organized what we recognize as modern manufacturing.

The efficiency experts and time-and-motion people have been replaced in the popular and political imagination by software coders and semiconductor manufacturers. Somehow, with enough money and will, it is hoped that they will solve the Ukraine War munitions crisis.

Maybe. Probably. Nevertheless, there will be more munitions crises in the future. It’s all in the nature of arms innovation and production. The creation of new and innovative weapons designs requires flexibility and open-ness to change. In contrast, high volume serial production, whether of arrows, artillery shells, or precision munitions requires fixed automation, large and readily available stocks of parts and material as well as skilled labor in the right place and time.

In between periods of intense warfare, production and stocking of munitions becomes over-expensive, annoying and even dangerous thanks to the aging and decay of parts and materials. Keeping alliance partners aligned on boring issues such as parts and specifications standards, decision processes and which will be the politically favored production facilities is not easy.

Actually, you can be sure that there will be yet more munitions crises after the Ukraine or China “questions” come to an interim solution. Human nature doesn’t change.

So, enjoy the Fourth of July (or Fourteenth of July) fireworks for the entertainment of pretend war that they are. In America, both traditional gunpowder fireworks and the light drone displays that are supplementing or replacing them are mostly made in China.

And also keep in mind that all wars must end…eventually.

HAPPY FOURTH OF JULY!!!

It will be curious to see how far Comrade Xi wishes to turn the screws on his American friends when it comes to the provision of processed rare earth elements. Rather remarkable comment from the CEO of Raytheon that 'there is no alternative'.

Fascinating and in depth look at historic lack of preparedness that seems to occur with such regularity. Do they learn this at West Point?